There are few public landscape features as ubiquitous as the town square. Its origins are too ancient to trace, its utility as a flexible gathering spot so apparent and universal that it really is at the heart of what public space means. In Spartanburg’s case, it is the original downtown feature, with nearly every generation since expressing their priorities through what it has included or left out.

During Spartanburg’s first century, the public square had more in common with a Western movie set than the space we’ve all known. Unpaved, surrounded by wooden buildings, and with little more than a public well and a curfew bell, the square was otherwise kept wide open for wagons and crowds that would assemble each month for the sheriff’s auction and the occasional political rally. During the 1850s, chinaberry trees were planted on the square’s periphery and along some of the larger streets. Grass wouldn’t grow because horses not kept at the livery stables would eat it. Such was the square during Spartanburg’s backcountry village days!

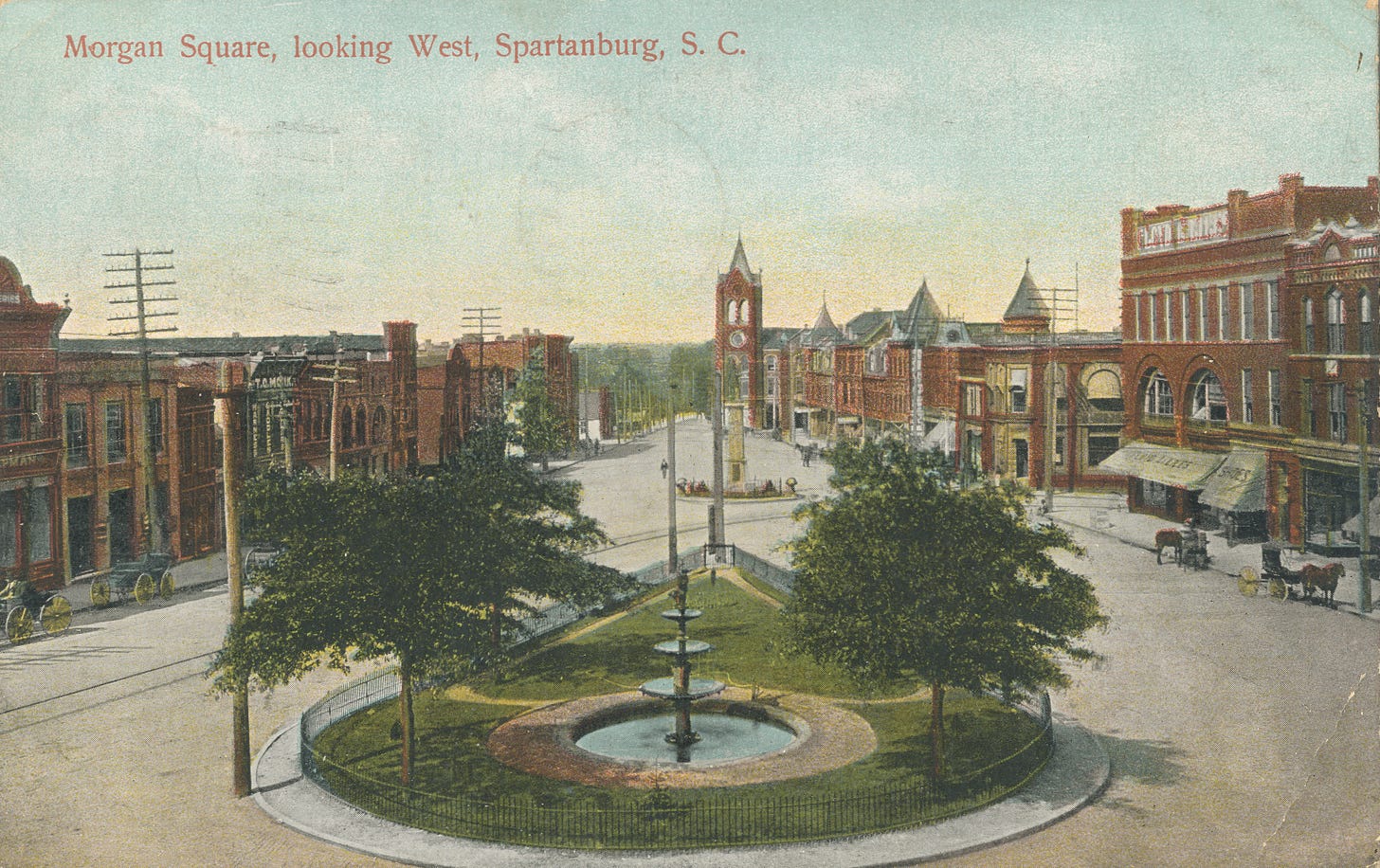

Increasing connections by railroads, markets, and influence brought new features to the square during the last two decades of the 19th century. The Opera House, featuring a clock tower, city offices, and a large public auditorium framed in the square’s western border beginning in 1880. National attention came the following year with the dedication of the Daniel Morgan Monument and the naming of Morgan Square. Soon after, electric arc lights replaced a handful of dim gas lamps and the square underwent a series of paving treatments, with crushed stone being replaced by brick pavers in 1900, the same year that an electric trolley system was installed.

There’s nothing like a grove of trees to make a space alive and inviting.

The first substantial greenspace in the square got its start in the 1880s when a multi-tiered iron fountain was added, surrounded by grass, and protected by a low iron fence. Folks poked fun at it, calling it “Mayor Calvert’s turnip patch.” Over the next forty years, this small park would be enlarged and trees added, forming a wedge of green surrounded by unmarked hardscapes. For a little while after World War I, the little park included a Coca-Cola-loving black bear that had been adopted as a mascot by Camp Wadsworth soldiers but abandoned when the camp was decommissioned.

The first threat to this greenspace came in 1919, when developers offered to buy it from the city and erect a 12-story flatiron-style office tower. Mayor Floyd was open to the idea, but the resistance won out, with many citing both traffic and aesthetic concerns, which had been stoked by the loss of many city trees earlier in the year during the installation of new street lamps.

Although the park survived that round, the increasing pressure of automobiles would dramatically remake the square during the mid-20th century. In the mid-1930s, the park gave way to a covered bus stop with public restrooms and an elevated bandstand, but by the early 1950s, this had all been removed and replaced with parking. Thus began a fifty year period in which the square’s space was nearly entirely devoted to the movement and parking of automobiles.

A 1959 plan called for the removal of buildings and extending the square to Church Street, the widening of lanes, and most controversially, the removal of the Morgan Monument. Only after significant public outcry was the plan altered to include the monument in the square’s new eastern end, but the sea of asphalt aesthetic remained intact. Several of those defending Morgan’s place in the square also lamented the emphasis on parking, with one commenter at city council saying, “Don’t you think it’s a dying shame to put a parking lot right in the center of the city?” And yet, for a long time, a parking lot it would remain. Although various proposals between the 1960s and 1990s called for reintroducing trees and a public assembly component to the square, it would remain devoted to parking and traffic until 2005, with only a handful of small live oaks planted in medians during the 1980s.

I remember people in those days speaking with envy about all the trees in downtown Greenville. When local folks were fretting over why their downtown worked when ours was struggling, those trees almost always came up. We finally got some trees of our own in the big 2005 redesign that brought the square to its current configuration. They have grown massive and so beautiful in the years since!

The fact that concerts, rallies, markets, and ice skating can also happen in a big flexible space at the beating heart of our downtown has also been so transformative. We need public spaces like that to gather and engage, but there’s nothing like a grove of trees to make a space alive and inviting. There’s room for improvement, and I can imagine worthwhile options that call for adjustments to the downtown canopy, but we shouldn’t lose sight that these trees have had sixteen years of good momentum that would be hard to replace. Let’s make sure that a mature, inviting greenspace remains a priority for our downtown showplace.

Brad Steinecke is a local historian with the Spartanburg County Public Libraries and serves as chairman of the City of Spartanburg's Board of Architectural Design and Historic Review.